As Haiti’s mass graves swell, the Haitian government estimates that the death toll will reach 200,000. If that proves to be true, it will place the 7.0 magnitude quake in the top seven most destructive earthquakes in recorded history.

While the people of Haiti are trying to figure out how to cope, people who watch from a distance are trying to figure out how to process this overwhelming natural disaster. Why did it happen? What sense can we make of it?

The explanations are numerous. Some say, it happened simply because of the moving of geological plates which form a fault line six miles below. Others blame global warming. Still others pin the devastation on Haiti’s class system which disfavors the poor, or on unfair international loan policies, or even the absence of the rule of law in Haiti. Pat Robertson said Haiti was cursed by God because its people swore a pact with the devil over two centuries ago through voodoo rites. Skeptics say it is a waste of time to search for deeper answers—the quake was simply bad luck.

At first it may seem to be inappropriate to talk about the “why?” of Haiti. This is a luxury for people who watch from a distance. Those in the midst of the crisis have less time for reflection. They need ministries of mercy more than armchair explanations. But for those of us who are far removed from this crisis, (and eventually for those who have lived through it), we must all eventually take some time to reflect on its meaning. To do this, it may help to recall the Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755.

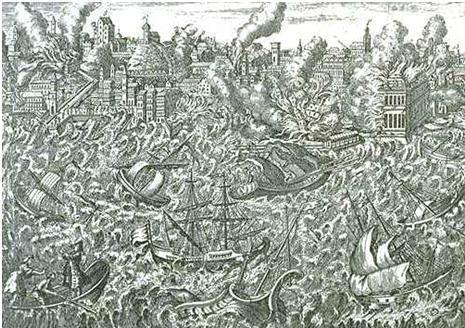

In that year, one of the world’s most beautiful cities was destroyed by a ten minute quake which was estimated to measure a massive 8.0-9.0 on the Richter Scale. It rocked Portugal and all of Europe. The fires and tsunamis afterwards brought even more destruction. The traumatic quake not only resulted in the death of some 70,000 people, but also raised deep questions in many people’s minds about God and the nature of this world.

Some people back then viewed the quake as an act of God which was punishment for Europe’s sins. Italian Jesuit theologian Gabriel Malagrida wrote that this was not just a natural event, but it was another instance of the wrath of God poured on Europe because of her “abominable sins.” In light of this event, he said, “it is necessary (for Europe) to devote all (its) strength to the task of repentance,” (AN OPINION ON THE TRUE CAUSE OF THE EARTHQUAKE).

Protestant preacher John Wesley agreed. “Is there indeed a God that judges the world” he asked. Wesley was convinced that God was not pleased with the “covetousness, ambition, injustice, luxury and falsehood” that had infected every rank of Europe’s people. He also mentioned the bloodshed from the Portuguese Inquisition, along with its plundering the new world’s inhabitants for stores of gold.

In a tract called, SOME SERIOUS THOUGHTS OCCASIONED BY THE LATE EQARTHQUAKE AT LISBON IN 1755, Wesley said, “it is not chance which governs the world.” He asked “does not God work by natural causes?” “Has his providence nothing to do with it?” He was convinced the Bible says that all things serve him. Even natural causes are under the direction of the Lord of nature.

Other people in Europe were not so sure. Deists insisted that God is not involved in the world in this way. He does not intervene in the physical world, they said. The Enlightenment’s concept of nature as an intelligible, machine-like world precluded any kind of divine intervention in the physical world—be it miracle or divinely ordered judgments. Baron d’Holbach, in his book THE SYSTEM OF NATURE (1770) wrote that the world is an “uninterrupted succession of causes and effects.” Nature is “entirely destitute of goodness or malice.”

Still others took a more skeptical line. The French satirist Voltaire (Francois Marie Arouet) claimed that such disasters are not the result of eternal laws, nor are they judgments on people. In his book, CANDIDE, among other things, he attacked the idea that an earthquake could have any theological explanation whatsoever. Voltaire ridiculed the theologians and preachers who spoke of an earthquake being a divine judgment on a society because of its sins.

In the wake of the earthquake in Haiti, I am struck by the fact that some things never change. We are still having earthquakes. And we are still hearing all kinds of explanations about what might be going on. Many in the press and the blogosphere are savaging Pat Robertson for his comments. Some are even invoking Voltaire—saying that theological explanations are out of bounds when it comes to assessing the ruins because there are no ultimate explanations of what is going on.

Even if Robertson’s wisdom and time are questionable, I for one am not ready to accept that.